From Variety

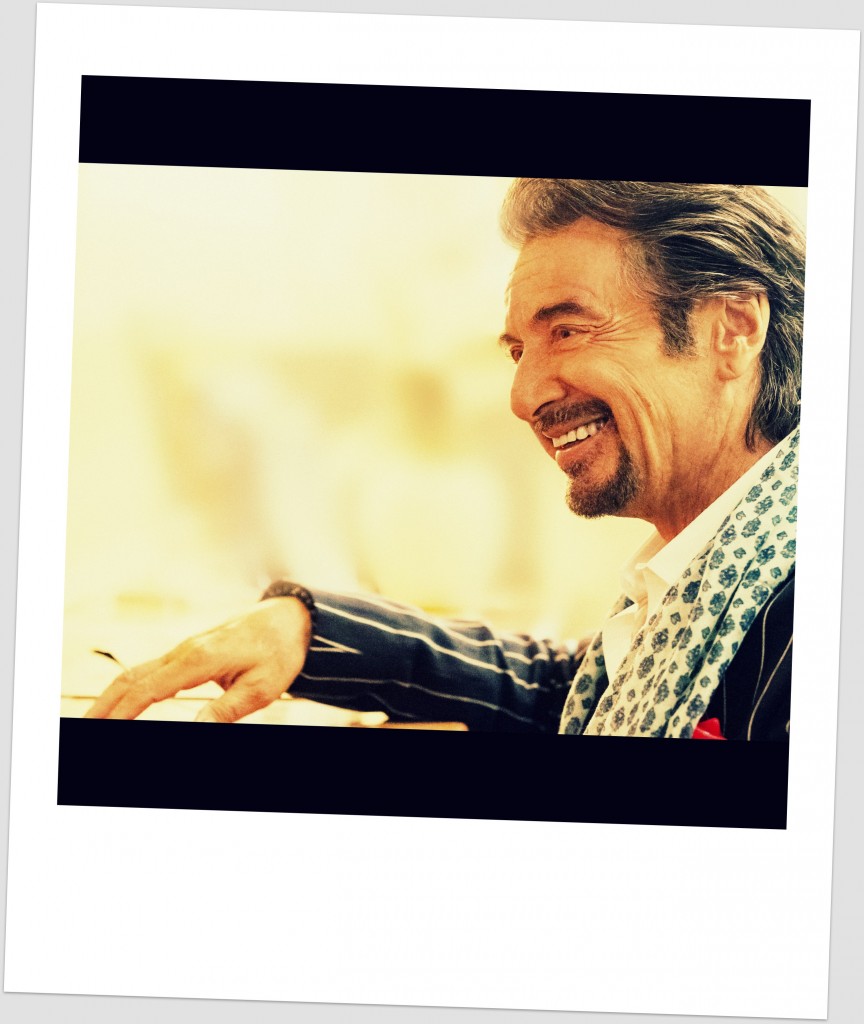

With his tufts of gravity-defying, shoe-polish hair and burnt-orange tan, Al Pacino has been sporting the look of a glammer-than-thou aging rock star for so long now that it’s only fitting he’s finally gotten around to playing one — which he does, exceedingly well, in “Danny Collins.” For his directorial debut, screenwriter Dan Fogelman has crafted a familiar late-in-life redemption narrative, made surprisingly palatable by Pacino’s winning comic bravado, a superb supporting cast, and currents of real feeling that cut through the expected bromides about the emptiness of fortune and fame. Though it’s unlikely to score quite the same home run with the Social Security crowd as the Fogelman-scripted “Last Vegas” did ($134 million worldwide), this March 20 opener should leave the staff of new distributor Bleecker Street humming a happy tune.

With his tufts of gravity-defying, shoe-polish hair and burnt-orange tan, Al Pacino has been sporting the look of a glammer-than-thou aging rock star for so long now that it’s only fitting he’s finally gotten around to playing one — which he does, exceedingly well, in “Danny Collins.” For his directorial debut, screenwriter Dan Fogelman has crafted a familiar late-in-life redemption narrative, made surprisingly palatable by Pacino’s winning comic bravado, a superb supporting cast, and currents of real feeling that cut through the expected bromides about the emptiness of fortune and fame. Though it’s unlikely to score quite the same home run with the Social Security crowd as the Fogelman-scripted “Last Vegas” did ($134 million worldwide), this March 20 opener should leave the staff of new distributor Bleecker Street humming a happy tune.

This is the second time in a year that Pacino has played a celebrated star in the throes of an identity crisis. Only, where “The Humbling’s” Simon Axler was a Broadway legend starting to lose his lines (and his grip on reality), Danny Collins is a music-world icon who long ago lost his artistic integrity — a subject which, given the general trajectory of Pacino’s movie career over the last decade (from grade-Z action fare like “Righteous Kill” and “88 Minutes” to the Adam Sandler debacle “Jack and Jill”), makes this new role seem even closer to home. The Collins we first meet in Fogelman’s film — in a brief, “Almost Famous”-ish prologue set in 1971 — is an earnest young singer-songwriter in the Bob Dylan/Jim Croce mold (played by Eric Schneider, a reasonable doppelganger for the “”Panic in Needle Park”-era Pacino). By the time we jump ahead to the present day, he’s become a kitsch pop icon with a signature sing-along anthem (“Hey, Baby Doll”), a third volume of greatest hits on the charts, and a young bimbo fiancee (Katarina Cas) on his arm. In the span of 40-odd years, Bob Dylan has become Neil Diamond.

It’s around this time that Danny’s longtime (and long-suffering) manager (the redoubtable Christopher Plummer) gifts him with a most unexpected piece of fan mail: a letter from Danny’s idol, John Lennon, penned in 1971 but lost for decades in the hands of a nefarious journalist (aren’t they all?) and a private collector. The message is a predictable “stay true to yourself” encouragement, along with an invitation for Danny to phone the ex-Beatle for a private chat. And it is this letter, “Danny Collins” asks us (not entirely convincingly) to believe, that sinks our hero into an existential funk, wondering how his life — and career — might have fared differently if he’d received Lennon’s letter in a more timely fashion.

In fact, there was a real Danny Collins, or rather a real Steve Tilston, a British folk singer who, in 2005, received just such a letter, written by Lennon in response to an interview the 20-year-old Tilston had given to a now-defunct music magazine in which he worried that commercial success might corrupt his artistry. But as an onscreen text at the start of Fogelman’s film states, “Danny Collins” is only “kind of based on a true story a little bit,” which means it’s safe to assume that the real Tilston (who’s credited as a consultant here) did not subsequently set off on a cross-country odyssey to meet the adult son (Bobby Cannavale) he fathered with a groupie back in the day, or hole himself up in a suburban New Jersey Hilton while trying to get back in touch with his songwriting muse.

But “Danny Collins” is a movie after all, and one that on its own warm, fuzzy terms offers a few modest surprises. With his basic setup in place, Fogelman could have easily let things coast along on heart-tugging autopilot, with all the expected sermonizing about how what really matters in life are the things money can’t buy. But Fogelman is smarter than that and so are his characters, especially Cannavale’s Tom and his no-nonsense wife, Samantha (Jennifer Garner), who initially resist Danny’s dramatic intrusion (complete with football-field-sized tour bus) into their placid suburban lives, but soon realize that there are certain advantages to having a rock star in the family — like jumping to the front of the line for an elite Manhattan school specializing in the needs of children like their ADHD-afflicted daughter, Hope (Giselle Eisenberg).

Cannavale, who can sometimes overdo his Italian-American working-stiff affect, is terrific as a man who’s spent so much energy trying to become the man his own father never was that it’s left him, at 40, as weary and worn-down as someone twice his age. But even Pacino is dialed way back from the scenery-pulverizing histrionics that have typified his post-“Scent of a Woman” career. Not unlike Collins himself, the actor has veered dangerously close to self-parody on more than one occasion with his outsized gestures and bellowing line readings, but he seemed renewed as a performer in his recent collaborations with Barry Levinson (“You Don’t Know Jack” and “The Humbling”) and in David Gordon Green’s “Manglehorn,” and he does again here, especially in the scenes with Cannavale, which go beyond the expected “you were never there for me” mawkishness. Sometimes, the two characters don’t say much to each other at all, but we know exactly what each of them is feeling. Watching Pacino in this role, you can see that he knows what it means to feel soulless and depleted as both an artist and a man, and he isn’t afraid to share that with an audience.

Of course, you don’t got to a movie like “Danny Collins” expecting to see one of those bleak, dark-underbelly-of-the-music-biz movies like “Payday” or “Crazy Heart” or “Inside Llewyn Davis,” and that’s certainly not what Fogelman sets out to deliver. But beneath the sitcom cutesiness and boldfaced sentimentality, the film manages to keep just enough reality coursing through to stay grounded. Even then, Fogelman doesn’t trust his characters (or his audience) quite enough to bypass such creaky contrivances as a potentially fatal illness for one character and, for Danny himself, a drug-and-alcohol addiction that the movie flicks on and off like a light switch whenever it’s convenient. And while Fogelman has written some nice, tart repartee for Pacino and Annette Bening (as a fastidious hotel manager in whom Danny sees a potentially “age-appropriate” love interest), the actress is around just enough to make you wish there were more of her.

Fogelman also fouls off what’s supposed to be the movie’s big climax, when Danny takes the stage for an intimate cabaret performance at which he’s supposed to unveil his first original compositions in years. The way the scene plays out, though, feels like a lazy narrative cheat, especially given a pop landscape in which older artists of all stripes lust after the very sort of back-to-basics career reboot that renders Danny inexplicably paralyzed with fear. A movie with no less a father of musical reinvention than Don Was (producer of lauded “comeback” albums for everyone from Bonnie Raitt to, yes, Neil Diamond) as its in-house music guru ought to have known better.

Still, Was has co-written (with Ryan Adams) a lovely original ballad, “Don’t Look Down,” that serves as Danny’s proverbial redemption song — and, unlike most such movie songs, sounds like it could have actually been written by the character. Elsewhere, Fogelman cycles through nine of Lennon’s post-Beatles recordings (including “Imagine,” which was at one point meant to be this film’s title), most of them used judiciously and without turning the soundtrack into an overly nostalgic baby-boomer hit parade.

Production

Crew

With

Tags: Al Pacino, Annette Bening, Bobby Cannavale, Christopher Plummer, Danny Collins, Imagine